Russian Science, An Insider’s View

The survey of around 100 experts was conducted at the end of 2015 in the process of designing a development strategy for Russian science and technology up to 2035 commissioned by the Russian Ministry for Science and Education.

Positive points

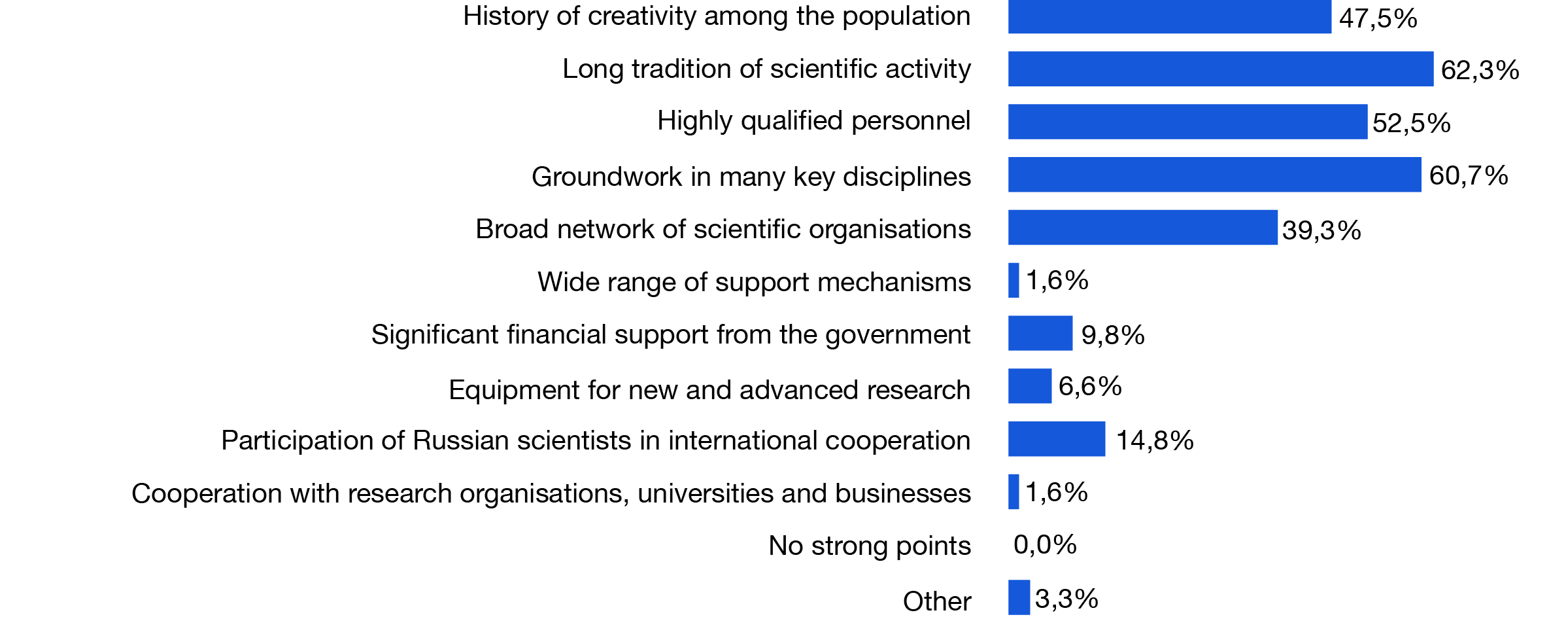

Many experts in the survey see the long tradition of research (62.3%), groundwork in many key disciplines (60.7%) and highly qualified personnel (52.5%) all as strong points in favour of Russian science. A significant number of respondents (47.5%) mentioned the nation’s history of creativity and inventiveness and broad network of scientific organisations (39.3%).

Diagram 1 - Question: “What do you think are Russian science’s strong points?”

In fact, Russia, unlike not only the newly industrialised nations (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia, etc) but some developed countries (Japan for example) too, has not had to create a national science force almost from scratch because it inherited one from the USSR. In the ensuing years the size of Russia’s national complex has shrunk significantly by it is still one of the largest in the world, after China, the USA and Japan in terms of scale. It is true that the number of researchers employed in the economy in Russia puts it behind 20 other countries. The situation is similar with domestic spending on research and development: while Russia is among the top ten in the general volume of spending, it occupies a very modest position according to the share of GDP (in 2014 this figure was 1.2% for Russia, but 3.93% for Israel, 3.55% for Finland, 3.41% for Sweden, 2.79% for the US) and to specific volume (according to the population). Nevertheless Russia maintains an enduring tradition of scientific activity which needs to be acknowledged and developed.

When considering how highly qualified Russian scientists are it is worth looking at the age structure and publishing activity of researchers. The situation with these indicators has developed in a contradictory way in recent years. On the one hand, the number of researchers under 39 has increased from 31.8% in 2008 to 43.3% in 2014, the size of the group of older scientists stabilized to some extent. At the same time, these clearly positive and reassuring turns were countered by staff cuts in the most productive age groups (40-49 from 16.7 to 13.2% and 50-59 from 26.3 to 20.6%). The problems with allocating highly qualified scientists in priority areas of socio-economic and S&T medium and long-term development have not gone away. Levels of productivity remain rather low. Although since 2011 the number of publications in scientific journals by Russians indexed in Web of Science has risen from 1.7% to 2.05% this figure is lower than it was at the beginning of the 1990s and significantly lags behind global leaders (France - 4.6%, Germany - 6.7% and China 17.6%). The gap is bigger in the level of cited publications. In recent years the government has made large-scale efforts to improve the situation but so far any changes for the better in Russia’s global position are happening very slowly.

Problem areas

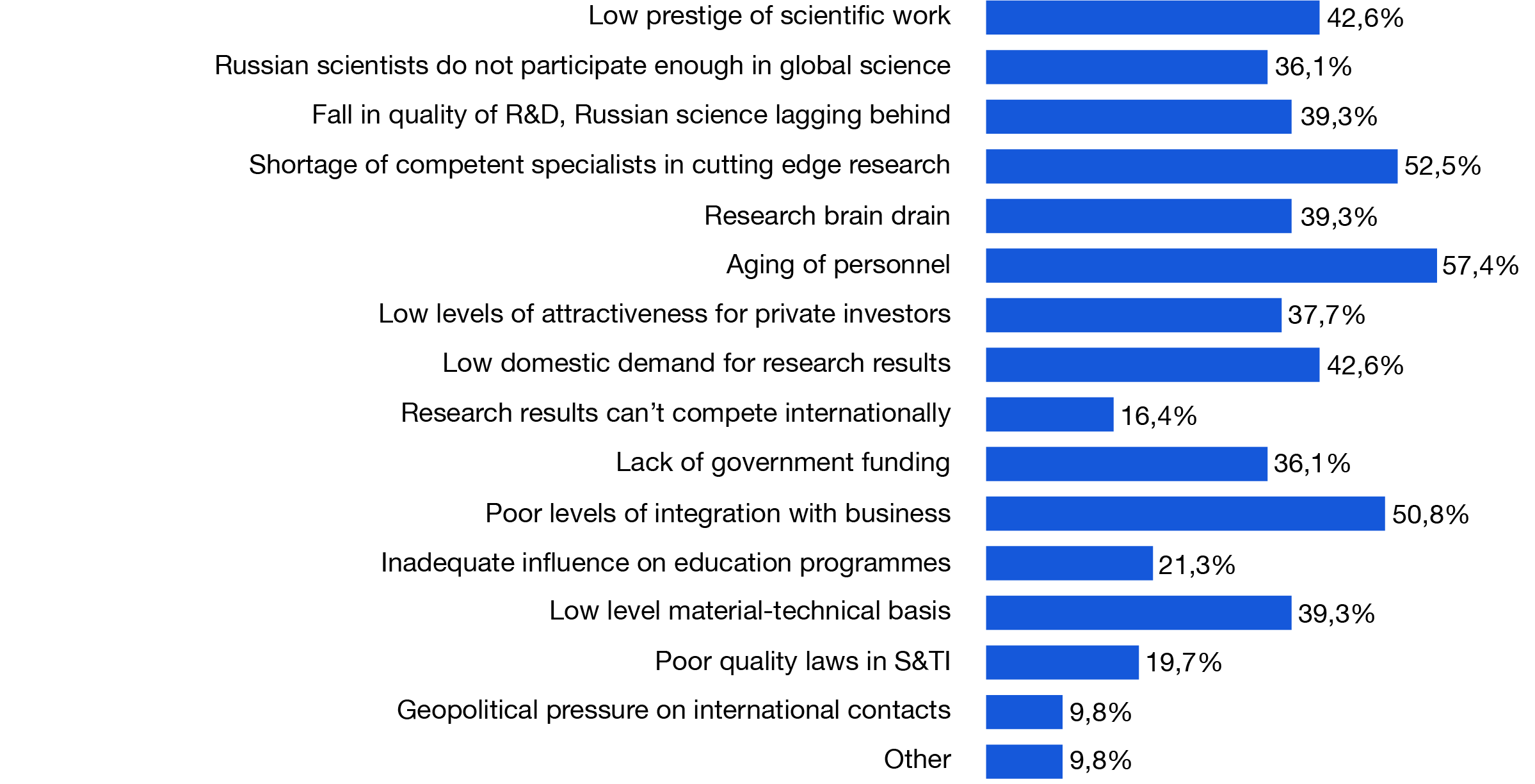

Respondents said that the most serious problems facing Russian science are the shortage of specialists with the skills to work in cutting edge science and technology (52.5%), the relatively high average age of personnel (57.4%), the low overall demand for scientists to produce results in the economy (42.6%) and poor levels of integration with business (50.8%).

Diagram 2 - Question, “Which do you think are the most serious problems which get in the way of improving Russian science?”

Effects and prospects

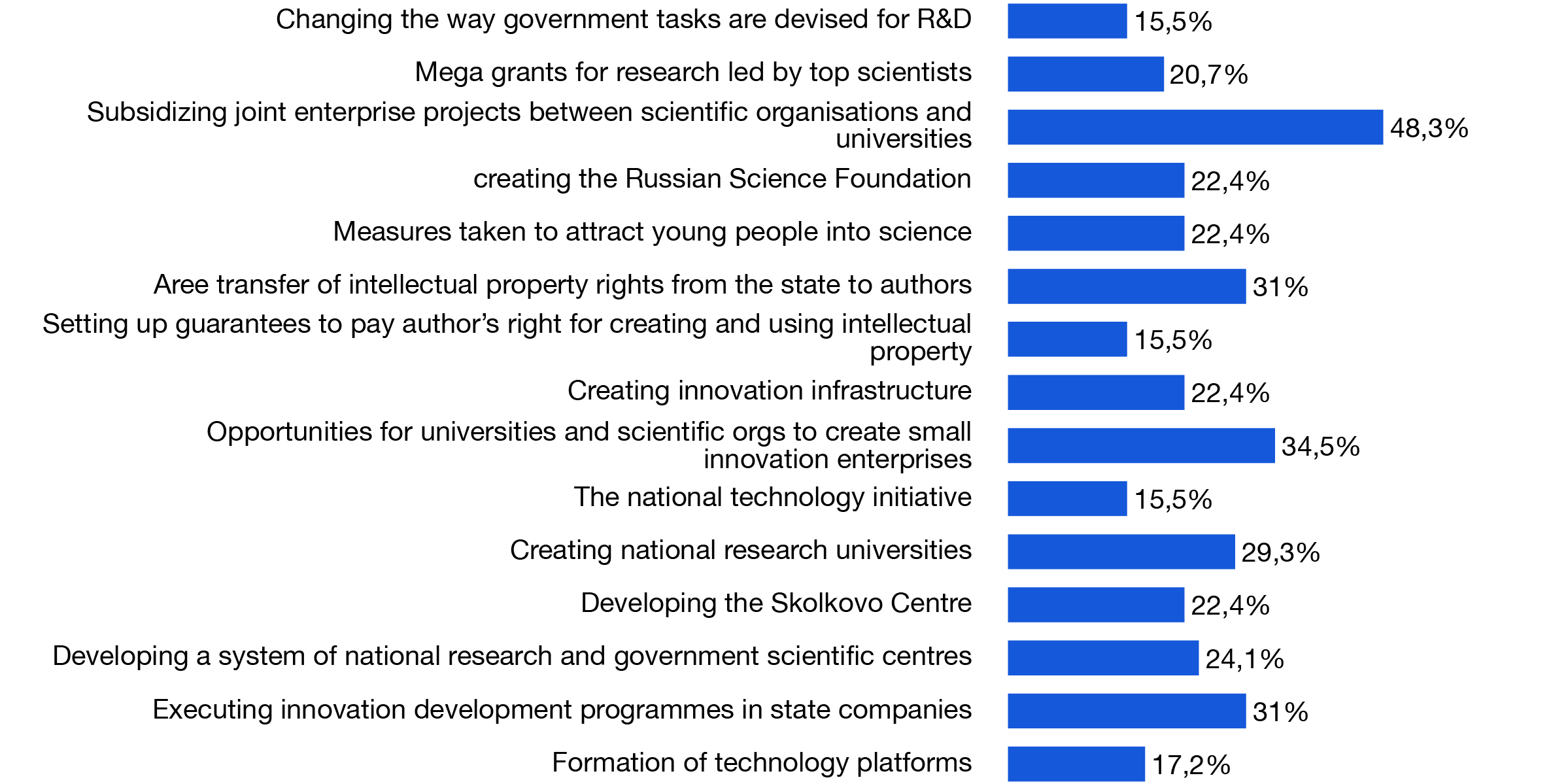

In spite of a number of serious initiatives to support Russian science in recent years, experts are rather cautious in evaluating the benefits. They think the subsidies (provided by a government initiative) for joint enterprise projects between scientific organisations and universities have been the most effective. Almost half (48.3% - see diagram 3) of respondents mentioned the positive results. This measure was intended essentially to develop cooperation between scientific organisations, universities and business which respondents had a rather low estimation of previously. Similarly, experts singled out the positive effect of big company innovational development programmes and new initiatives to cultivate a civilised intellectual property market in Russia.

Diagram 3 - Question, “Which measures introduced in recent years to regulate science have had a positive effect?”

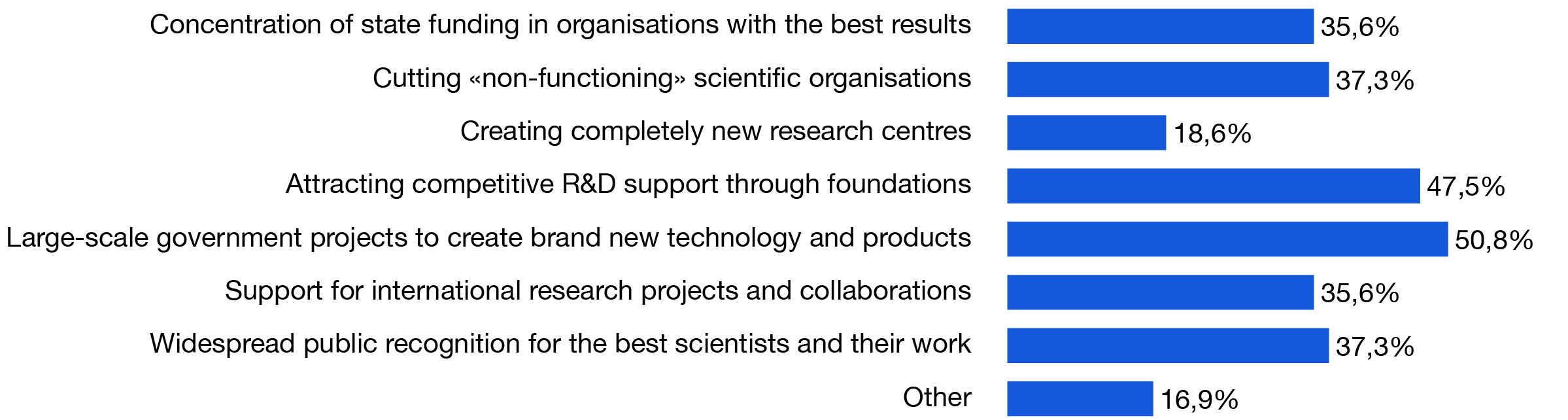

As far as prospects go, (diagram 4) respondents mentioned that large-scale government S&T projects, the development of a system of foundations to support science and institutional reforms had all contributed to guaranteeing the future of Russian science.

Diagram 4 - Question, “Which measures do you think have made scientific work more productive?”

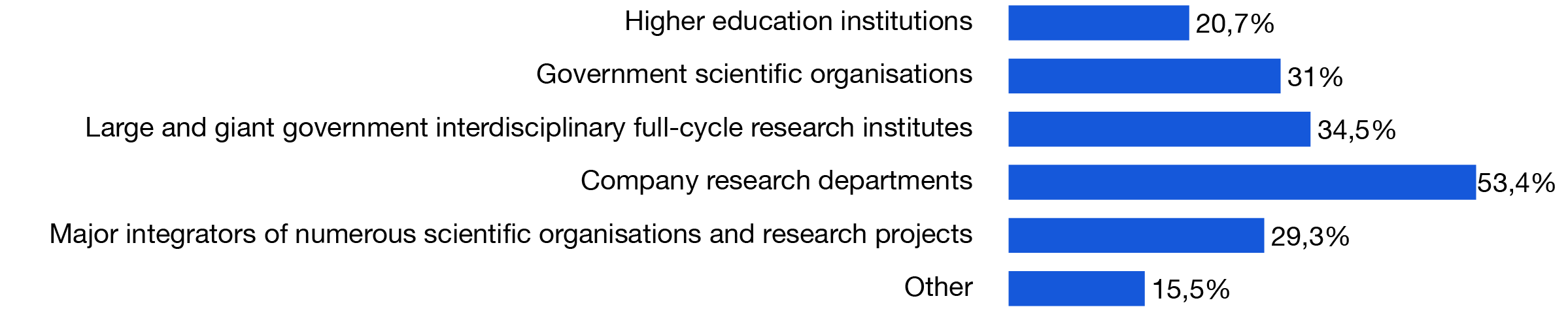

More than half (53.4%) of respondents placed their hopes for a breakthrough in science and its application in the establishment and development of research departments in innovation companies. This generally corresponds to an understanding of the essence of innovational processes as developed by economic theory and proved in practice. And although the role of business in research and development is lower in Russia than in several other countries (In 2014 the share of the enterprise sector in domestic spending on science was 27.1% (32.9% in 2000), in Germany it was 65.2%, in Italy, 44.3%, and in Brazil, 45.2%) the experts clearly see companies as potentially the most important player in science, technology and (especially) innovation (diagram 5).

Diagram 5 - Question, “Who in your view is most likely to provide a breakthrough in scientific research and its applications?”

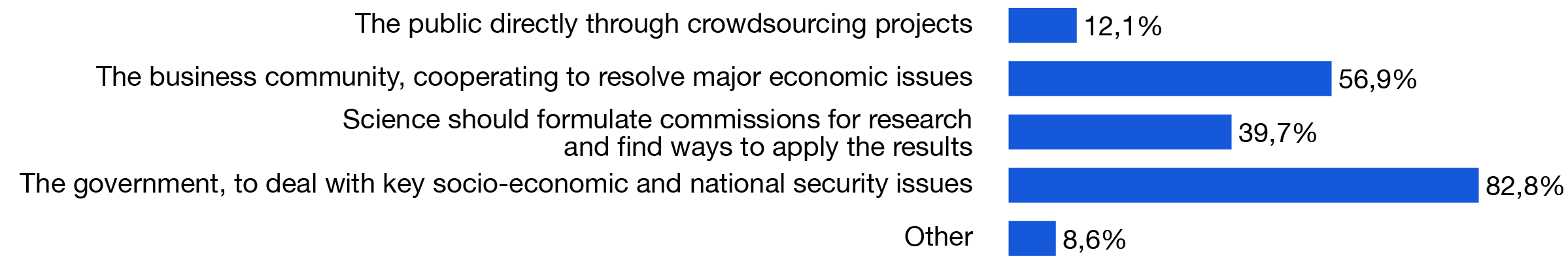

Most respondents (82.5%) believe the government is responsible for formulating commissions for science. More than half (56.9%) acknowledged the involvement of the business community in this process is essential. This view evidently reflects the long tradition of the state’s dominant role in financing scientific research in Russia, in its organisational structure and in other characteristics.

Diagram 6 - Question, “Who do you think should formulate commissions for science?”

And finally, two thirds of respondents (70.2%) in answer to the question what role does science play in Russia’s social and economic development, said R&D is the basis of national security, more than half (52.6%) said it is a source of intellectual and cultural development. 47.4% said science is the driver behind new sectors of the economy although 1 in 10 said they think the contribution made by science is insignificant.

One way or another the expert community supports and perpetuates the belief that science and technology play a key role in economic and social progress. They are anxious about how Russian science and the state will improve but they are of the opinion that it must behave consistently and systematically.

Authors: Mikhail Goland, Galina Kitova and Tatiana Kuznetsova